Where to begin? Salman Rushdie’s latest novel, The enchantress of Florence is one of those books-writ-large: its canvas is broad, its structure a little complex and it has a large character set. In other words, you need your wits about you as you read this one.

This is only my third Rushdie. Like most keen readers I read and enjoyed Midnight’s children, with its inspired exploration of the partition of India. I also loved his cross-over children’s book Haroun and the sea of stories. It is a true laugh-out-loud book. In fact, as I started this book I had a flashback to Haroun, not so much because of the subject matter but the light rather satirical if not downright comedic tone. It is very funny at times, particularly in the beginning.

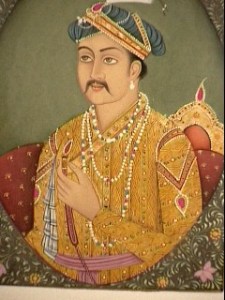

The novel is set in the 16th century and revolves around the visit of a young Italian, the so-called “Mogor dell’Amore” (Mughul of Love), to the Mughal emperor Akbar‘s court and his claim that he is a long lost relative of Akbar, born of an exiled Indian princess (Qara Köz) and a Florentine. The story moves between continents, with “Mogor’s” story about his origins in Medici Florence being told alongside that of Akbar’s court. The book is populated with a large number of historical figures – and at the end of it is an 8-page (my edition) bibliography of books and web-sites Rushdie used to research his story. They include social, political and cultural histories as well as fictional works such as Italo Calvino’s Italian folktales. One could wonder, at times, whether it’s a little over-researched, but perhaps that would be churlish.

The next question to ask is, What sort of novel is it? Is it historical fiction? Well yes. Is it a picaresque novel? Yes, a bit. Is it a romance? That too, a bit. Is it a comedy? Certainly. Is it a fable? Could be! What it is, under all this of course, is postmodern.

If I had to use one word to describe this book it would probably be paradoxical. On the second page of the story, the bullock cart driver who brings the stranger (our “Mogor”) to town, describes his passenger in these terms:

If he had a fault, it was that of ostentation, of seeking to be not only himself but a performance of himself as well, and, the driver thought, everyone around here is a little bit that way too, so maybe this man is not so foreign to us after all.

And thus the scene is set for a rather rollicking tale about people who either aren’t all – or don’t seem all – quite real, who play games with each other, who are perhaps more alike (“not so foreign”) than they are different, and who manipulate, fight, love and hate each other as they struggle to find (or understand or establish) their place in the world. In fact, at the end of the first chapter the sort of paradoxical story we are embarking on is made clear:

The visionary, revelatory dream-poetry of the quotidian had not yet been crushed by blinkered prosy fact.

In other words, as you read this book, keep your wits about you! And that is, I admit, what I found a little hard to do as stories, people, and ideas were thrown at me…and then taken back and thrown at me a different way. As I read books I tend to jot notes on the blank page/s you usually find at the end. My notes on this one are all over the place: Love, Power, Names and their mutability, Truth, Religion and Faith, Imagination and Reality, Stories, Nature of men and women, East versus West, and so on. The question now is, Do any of these tie together or form a coherent thought upon which to hang the book? I think there is, and it is to do with ideas surrounding imagination and reality. In Chapter 3, for example, we learn of Akbar’s love for Jodha, the woman he has conjured up for himself:

She was an imaginary wife, dreamed up by Akbar in the way that lonely children dream up imaginary friends…and the emperor was of the opinion that it was the real queens who were the phantoms and the nonexistent beloved who was real.

Their love is called “the love story of the age”, and the chapter talks about the border between “what was fanciful and what was real”. Love, and its power, is one of the driving forces of the novel, and, without giving anything away, the ending more or less unites the two ideas: the power of love, and the conjunction of imagination and reality.

But, truth be told, I’m having trouble writing about this book…and I think this is because, for me at least, it started off with a flourish but got bogged down, particularly when we moved from India to Florence. That said, it picked up again near the end. Here is Akbar in the last chapter:

Again, at once, he was mired in contradictions. He did not wish to be divine but he believed in the justice of his power, his absolute power, and, given that belief, this strange idea of the goodness of disobedience that had somehow slipped into his head was nothing less than seditious. He had power over men’s lives by right of conquest … But what, then … of this stranger idea. That discord, difference, disobedience, disagreement, irreverence, iconoclasm, impudence, even insolence might be the wellsprings of good. These thoughts were not fit for a king.

The word I used earlier in this review to describe this book was paradoxical and this is because almost every “truth” presented within its pages is met by an equal but opposite “truth”. And perhaps that is the biggest truth of all!

Salman Rushdie

The enchantress of Florence

London: Vintage, 2009

355pp.

ISBN: 9780099421924

You did well to read this. I tried, and gave up. I find Rushdie “difficult”, but not in a good way!

Your review has provided me with more information than I had before about this book however, and was a good read in itself

Well thanks Tom…I struggled a little with the book as you will have seen but I liked it nonetheless. It is so large in conception and rollicking in realisation. I wondered really whether my review made sense but I’m glad you got something out of it. (I did notice there wasn’t a Rushdie in your list – when I read a book and write my post I often then look at your lovely list to see whether you have done it too!)

Can someone please explain this book to me? If there’s anyway you could relate the book to the idea of cosmopolitanism and exile? Thanks I just really want to understand this book it’s just difficult.

Welcome, Beth, but I’m sorry that I can’t really help you as l read this book a long time ago. I guess I’d start with looking at definitions. As I recollect it’s quite a cosmopolitan book in the way some characters move between cultures / places and interact with each other. In this book, are cosmopolitanism and exile sort of opposites? Hmm, I’d really have to read it again.